Helicopter Parenting Makes Sense To Some, But Research Details All The Ways It Backfires

Professor Chris Segrin of the University of Arizona has seen what he dubs as the “the first generation of overparented kids” graduate into the world and concludes the prognosis isn’t good.

”The paradox of this form of parenting is that, despite seemingly good intentions, the preliminary evidence indicates that it is not associated with adaptive outcomes for young adults and may indeed be linked with traits that could hinder the child’s success,” concludes Segrin’s latest study, set to be published next month in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology.

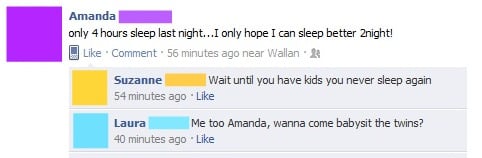

Segrin’s study says these parents routinely intervene on an inappropriate level, by offering unsolicited advice, removing obstacles and solving problems that kids should tackle themselves, according to Segrin “actually wind up as anxious, narcissistic young adults who have trouble coping with the demands of life.”

Other recent research finds helicopter parenting backfires and may damage children in other ways.

California sociologist Laura T. Hamilton that says that the more money parents spend on their child’s college education, the worse grades the kid gets. Another study by Virginia psychologist Holly H. Schiffrin finds that the more parents are involved in schoolwork and selection of college majors, the less satisfied their kids feel with their college lives.

The world can be a tough place. Even if you made all the right choices – picking the right neighborhood, with the right schools, and set him up in preschool with the right group of friends – all children will face adversity. There will be teachers who don’t like them, peers who will make fun of them, and goals they will not be able to meet on the timeline they might want to accomplish them. Even though it feels counter-intuitive to some parents, letting them fail or stumble is preferable to overparenting.

If children don’t learn how to navigate these stressful or real-world situations while they are living at home, where a parent’s support and guidance is easily accessible, they will find themselves lost even when they leave the nest.

Segrin’s latest papers relied on interviews with more than 1,000 college-age students and their parents from across the nation. They found that many of the young adult kids are in touch with their parents constantly, with nearly a quarter communicating by text, phone or other means several times every day and another 22 percent reaching out once a day.”There’s this endless contact with parents,” says Segrin, who doesn’t have children. ”I don’t think it’s just calling to socialize. A lot of it is, ”˜How do I?’ ”˜Will you?’ ”˜Can you?’ They are still quite reliant on their parents.”

Parents can instead give their children enough freedom to face setbacks on their own, with support as they experience the consequences of their actions and guidance for how to handle it differently in the future. In short, let them make the tough decisions because loving your kids doesn’t mean making their time at home as easy and obstacle free as possible.

(photo: Tissiana Kelley/Shutterstock)