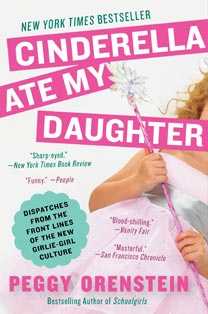

Exclusive: Peggy Orenstein Tells Mommyish Why Those Girly LEGOs Should Give Parents Pause

Author and journalist Peggy Orenstein received massive praise for her investigative look into princess culture with Cinderella Ate My Daughter: Dispatches From the Frontlines of the New Girlie-Girl Culture. A New York Times best-seller and now available in paperback, Cinderella At My Daughter offers an analytical look into the origins of modern princess obsession along with a first-person navigation of beauty pageants à la Toddlers & Tiaras, the impact of the term “tween,” and how teaching girls to be “sassy” is just a PG-13 term for “sexy.”

It’s been nearly a year now since Cinderella Ate My Daughter was released. How have parents responded to your criticisms of princess culture?

The response has been tremendous and gratifying. I think more parents are seeing the connection between the pink culture of little girlhood and the diva-narcissist-beauty obsessed culture that is drifting increasingly younger.

I often hear from readers who say that this push towards princess-conscious parenting makes them feel like bad parents for having princess-obsessed daughters. In my own work on Mommyish, I always try to convey that there is a way to responsibly parent little girls with princess obsessions by being critical of what princess culture espouses. What’s your response?

I think we parents””moms especially– are so anxious, so prone to self-blame, so easily convinced that if we haven’t achieved some ”ideal” we’re ”bad” parents. Which is part of the whole perfectionism complex I discuss in the book. But I wrote the book from the perspective of a mom, and a mom who was constantly torn and conflicted and ambivalent and hypocritical””like all of us””and who is doing the best she can. So there is no blaming or shaming of parents. I don’t think there’s anything I say””though there may be things people have said ABOUT what I say””that should or would make anyone feel like a bad parent. If anything, I would think the knowledge and dots connected in the book should help them feel empowered both as individual parents and to make change in their communities if they want to.

But I think I’m pretty clear all along that things are out of whack, so the answer is, yeah, to limit what comes into the house but also to expand girls’ ideas of what it can mean to be a girl. Not just with the gender-neutral stuff but also with playthings and images that present more powerful, interesting, complex messages. One of my favorite examples is that when my daughter was four we started reading child-friendly Greek myths and she went trick-or-treating that year as Athena. So she still got to wear a cool gown-type thing and a silver laurel leaf wreath on her head but the symbolism and message of Athena, goddess of war and wisdom, is very different than the Disney Cinderella.

Look, the Princess industry is a multi-BILLION dollar industry. It’s going to affect you. It’s going to get into your home. And to totally beat yourself up about that would be defeatist. Instead, like I said, limit where you can and fight fun with fun, by which I mean find other images and playthings that you can infuse with as much fun, excitement and fantasy as the princess stuff. I have ideas on my web site if you click on the ”resources” button. That way you don’t have to re-invent the wheel.

But really, when you ask that my mind doesn’t even go to the issues in the book. I think more: why do we women especially take any challenging topic of discussion as an indictment of us as mothers?

We recently wrote on LEGO launching their new line for girls and the petition by parents. Some parents I heard from dismissed the debate as hoopla and embraced a product that their little girl would like to play with. What are your thoughts on the new line for girls and the message it ultimately sends girls?

In my op-ed about it for The New York Times, one of the points I make is that the “Friends” line discourages cross-sex play and if you look at the old LEGO boxes from the early 1960s there are girls and boys playing TOGETHER on the cover. And we have to ask what is lost with what has become an aggressive hyper-segmenting of the toy market, beyond anything we even saw when we were kids. It’s beyond Mad Men. It’s beyond what was going on in the 1950s. And given the vital importance of cross-sex play (understanding that mostly preschoolers will play with their own sex) which I discuss in the article that in itself should give parents pause.

I once attended a talk you did in which you described yourself as a pro-sex mom who is anti-sexualization. How do you walk that line with your own daughter and what advice do you have for parents struggling to do the same?

Well, my daughter is still young. She’s in third grade. I think that the issues will become more challenging in the next few years. But honestly? That’s what my next book is going to be about, so interview me again in, oh, 2015 when it comes out and I’ll have a lot to say about that.

But essentially what I meant by being pro-sex and anti-sexualization was that sexualization encourages girls to be desirable while disconnecting them from their own desire. It’s the performance of sexuality rather than the felt experience of it. And that is the antithesis of what I want for my daughter.

The sexualization of girls is getting more and more attention in the media these days and I often worry that the media narrative is often to lock girls up, stifle them, and shelter them from everything in our culture. Caitlin Flanagan recently argued in her book Girl Land that girls shouldn’t even have internet access in their bedroom and that Planned Parenthood encourages oral sex. How do you respond to this assertion that girls should have less information at their disposal?

Again, it’s exactly those questions that are inspiring me to write the next book. I don’t think that’s the way to go, obviously, but I want to do some deep thinking and writing about how to separate the threads of sexualization and sexual agency, what authenticity means, how we can guide girls, etc. So I’ll get back to you on that one. I do think those questions are pivotal, obviously.

When it comes to the sexualization of girls, the onus appears to always be on her to not dress a certain way or to not have certain products. But how do you think boys and the parents of boys should also be included in the conversation of sexualizing girls?

Gosh, I so wish they would. And I know some do. But I so often get from parents of boys, ”Whoo! I’m so glad I don’t have to worry about this!” And I say, really? Are you thinking your son is not going to ever go to school with, work with, partner with, or have children with a girl? Because if he is, you better be talking to him about the images of girls and women out there and how that affects his relationship to the other sex and theirs with him. It goes both ways, affecting what girls expect from boys and what boys expect from girls.

(photo: peggyorenstein.com)